I left a part of myself in Afghanistan during my deployment as a Canadian soldier. That's why it hurt so much to see everything fall to the Taliban again after the coalition forces pulled out in 2021.

I was 18 when I joined the Canadian Armed Forces and deployed soon after. My tour started in February 2008, during the low fighting season. The level of violence dropped annually in the spring when nearly every available hand was harvesting the opium crop to pay for the year's expenses, including ammunition.

By late summer, high fighting season began. Enemy activity increased and life became more dangerous. But near the end of my seven months in Afghanistan, I felt I had tempted fate and would go home unscathed — emotionally and physically still in one piece.

Fate had another plan.

Kandahar Airfield was the main military base in the southern part of Afghanistan. Afghan civilians would often come here seeking help from the field hospital after a suicide bombing or other violence, and as part of the infantry, we were often required to accompany them.

This particular evening, I was on security detail and was called to accompany a middle-aged man whose daughter had been shot in the head by the Taliban. We were told she was shot for simply wanting to attend school.

Initially, the father appeared to be in good spirits and even hopeful but the details of his daughter's condition sounded bad. I was worried, and tried to distract him in the makeshift waiting room.

I pulled out my iPod video, showed him how it worked and let him explore its contents.

After what felt like an eternity, the doctor came in with a Pashto interpreter. They led us to where his daughter lay on a hospital bed, and it's a horrific sight that's burned into my memory.

I could tell she was human by her arms laying on the blankets. But her face was a mix of bandages, wires and a tube. Her father broke down crying.

After that, the only sound I remember was the beeping of the heart monitor.

The next day, our sergeant asked how she was. But due to patient confidentiality, we never got an answer. It was a gunshot wound to the head, so it was unlikely that she would have survived.

Counselling was offered but I didn't pursue it. I just wanted to stop thinking about it.

When I came back to Canada, I stayed involved with the army reserves part-time for the next decade and worked retail jobs to pay for university. I tried to adapt to life in Calgary and to act "normal." I rarely talked about the things I saw in Afghanistan.

That strategy mostly worked. At least, until August 2021 during the fall of Kabul.

I watched reports on the evening news, stunned at how quickly the Taliban took over again. Seeing images of the panic and chaos made me feel I was right back there — back in a desert that I never really left. The feelings of rage and helplessness took over. There was nothing I could do.

By then, I had left the military and, during that difficult summer, I was working with the Canada Border Services Agency at a very different airfield: the Calgary International Airport.

One of my roles was to help process the many emergency flights of Afghan refugees that started to arrive in our country. Once again, I found myself face-to-face with the Afghan people.

As each plane load of refugees arrived, I went through their visa, passport and other documents to confirm their identity.

I had just completed this verification process with an Afghan family when the youngest daughter — a school-age girl — removed her surgical mask, looked up at me and, in perfect English, thanked me.

I suddenly felt at peace. It was as if those two moments in time, 15 years apart, were related. To me, it was as if the humanity that was lost all those years ago had been restored.

I've been trying to make sense of this. Why did seeing the second girl's face make such a difference? I think it comes back to my favourite Emily Dickinson poem, Hope Is the Thing with Feathers.

"Hope" is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all - ...

The second girl will hopefully grow up in Canada without the fear that someone will harm her for simply going to school.

Her presence here doesn't change what happened in Afghanistan to that other girl or the countless innocents. But after all the darkness that I had witnessed, it meant a lot to me.

She helped me find that hope.

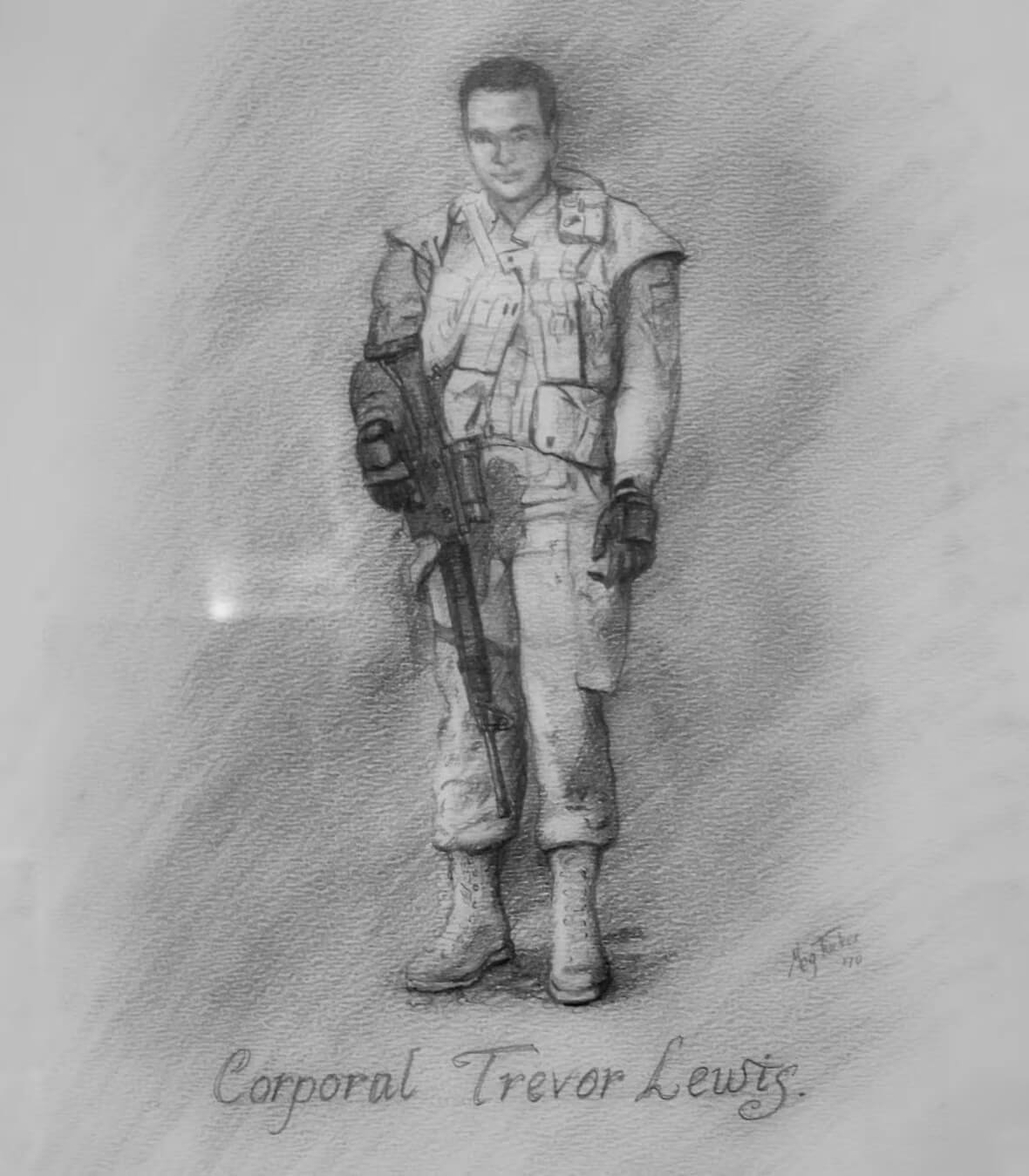

Trevor Lewis was a corporal in the Canadian Armed Forces and deployed to Afghanistan in 2008. He now works with the Canada Border Services Agency.

Trevor wrote this story as part of the 2023/24 Veterans' Writing Workshop, and it was featured on the CBC website as part of the First Person series.